|

|

|

|

|

|

Shark Info (06-15-1999) |

Author |

|

Intro: |

Shark Info |

|

Main article: |

Shark Info |

|

Article 1: |

Dr. T. E. Hopkins |

|

Article 2: |

Dr. A. J. Godknecht |

|

Article 3: |

Dr. E. K. Ritter |

|

Fact Sheet: |

Dr. E. K. Ritter |

|

Underwater Parks: Economic and Ecological AspectsUnderwater parks might help marine animals to survive. Report by Shark Info

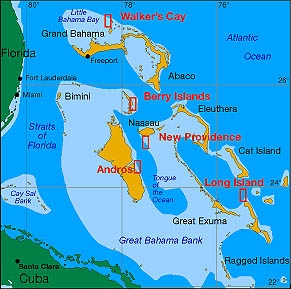

More and more governments are learning that living animals contribute a greater share to a country's economy than dead ones. This evolution in thinking began with the wildlife parks in Africa and is now extending to the oceans. Undoubtedly a big attraction for such underwater nature reserve areas is the shark. Economic Interests: Example BahamasThe recognition that it is economically and ecologically more meaningful to use living animals as a tourist attraction rather than to approve overexploitation of their population in order to retain some jobs is gaining foothold worldwide. The market value of an average-sized shark is currently about 10 dollars, but this cannot be compared to its touristic value. In the Bahamas this recurring value is estimated to be approximately 15,000 dollars per shark annually! What causes such a drastic difference? More and more people choose to spend their vacation at ocean areas marked by an intact underwater environment, biodiversity and associated water quality. In fact, people are even willing to pay a little more for such an intact environment. The Bahamas represent such a touristic magnet which annually attracts around 3.2 million swimmers and divers from all over the world. Situated on the flat plateau in front of the U.S. coast, the islands are treasured by divers since the area is well-known as being one of the best shark regions in the world. The waters surrounding the Bahamas are not only inhabited by a large number of sharks but also by a rich number of shark species, making it a rare underwater region (species list). Bahamian authorities thus estimate that around 40% of all divers who visit the Bahamas do so primarily to view sharks in their natural environment. Insufficient protection of natural resourcesThe large number of sharks and their diversity of species translates into real gold in the Bahamas. However, this wealth is significantly endangered due to local fishermen and especially foreign fishing boats whcih catch sharks in Bahamian waters. In the early nineties, the government passed a law forbidding longline fishing, but this law offers only a minimum of protection. Insufficient resources are available to control longline fishing and it should not come as a surprise that more and more unpunished transgressions are registered. It is thus absolutely necessary to establish protected zones, because commercial fishing vessels - both in the Bahamas and elsewhere - ignore any laws and quite often fish entire underwater areas dry in night actions. In Walker's Cay, for example, one such night action resulted in the loss of forty sharks or almost half of the one hundred sharks located in the region. These were sharks which many visitors had been able to observe during many dives, and which many people almost got to know "personally". All of the animals were later found with their fins cut off in the vicinity of Walker's Cay. Underwater parks as an economic factorEstablishing underwater parks are a first attempt to

protect regions which may be hard to control by other means. The control of fishing bans and

conserving the environment would be transferred to local authorities who have a more direct

interest in maintaining regulations than remote government offices. Underwater parks also

have many advantages. Economically, they could be a blessing for many regions as tourist

attractions which are protectable and where the variety of animal life is preserved.

Furthermore, the transfer of executive powers to local authorities could have the advantage

of leading to much improved enforcement of fishing rules because they know the areas very

well and could prevent any form of fishing with effective sanctions. This appears to be a

simple enough formula - right? Still, using the example of Walker's Cay, Abaco Islands, it

is obvious that a lot of persuasive powers will still have to be employed, not only with

government offices but also with local inhabitants. Nature reserves serve not only tourismBut why are underwater parks even needed? Has the Bahamian Government not solved the problem with its already longer existing prohibition of destructive "longlining"? The answer is absolutely no, for "longlining' is only one aspect. In reality, the entire ecosystem needs protection. In this case, economy and ecology go hand in hand. Underwater parks allow local authorities to handle any poaching and eventually punish the guilty. Protected marine areas guarantee that the ecosystem and refuge for many animal species is retained and maintained in a usable form. In other words, such parks should not only be seen from the viewpoint of serving tourists, but also under economic, conservation and biological aspects. The protection of certain ocean regions must thus be subject to precise guidelines. Otherwise the danger exists that such parks are misused by purely economic interests. Unfortunately, the rising tide of ecotourism produces more and more black sheep. Uncontrolled shark feedings for show purposes condition sharks and may actually provoke accidents. This should also be prevented, along with any excessive negative effects on the ecosystem arising from touristic overuse. Only strict guidelines and competent, incorruptible control authorities can inhibit such misuse. In that way, underwater parks will not only benefit the region but will also support science and the economy. The Shark Foundation, for example, supports research projects which study the natural migration paths of sharks and their biological behavior. The U.S. Shark Foundation, the affiliated American organization, was founded to support and further promote the Walker's Cay Underwater Park as well as other similar endeavors.

Unfortunately, while the benefits of such parks as Walker's Cay are obvious, the involved authorities are often very indifferent and the outdated opinion which considers the ocean as a continually replenished source of economic gains still prevails. As a result there is often a tendency to feel that such projects are only slightly or not at all necessary. Today, plans exist to set up underwater parks in the southwest of New Providence, the northern end of Long Island, and parts of the barrier reefs fronting Andros and Berry Island. These plans were submitted to the Bahamian Government, but a possible decision date remains vague.

May be published only by indicating the source: Shark Info |

|

|

|

|

|

|||||